The ink is barely dry on a domestic violence protection order.

Two Seattle police officers are escorting the woman who filed for that order hours earlier on a rainy Monday morning from the King County Courthouse.

The officer’s mission is to remove all firearms from the woman’s home so that that the guns are nowhere to be found when the woman’s allegedly abusive husband returns.

“There’s no other guns in here?” Officer Sean Hamlin asks the victim as he surveys the apartment. “He doesn’t keep a pistol in the nightstand or anything?”

Hamlin and Sgt. Dorothy Kim emerge with two tactical-style rifles that they’ve seized, weapons that they are legally allowed to take under a “weapons surrender” order issued by a judge.

“The order was issued half an hour, or an hour ago,” Hamlin says.

The woman, who asked that we not identify her for safety reasons, claimed her husband had knocked her to the ground the night before and hit her in the face. In her petition for a domestic violence protection order, she cited a fear of the guns that he owns.

The rapid response to her weapons surrender order might not have occurred if she filed a protection order just a few months ago.

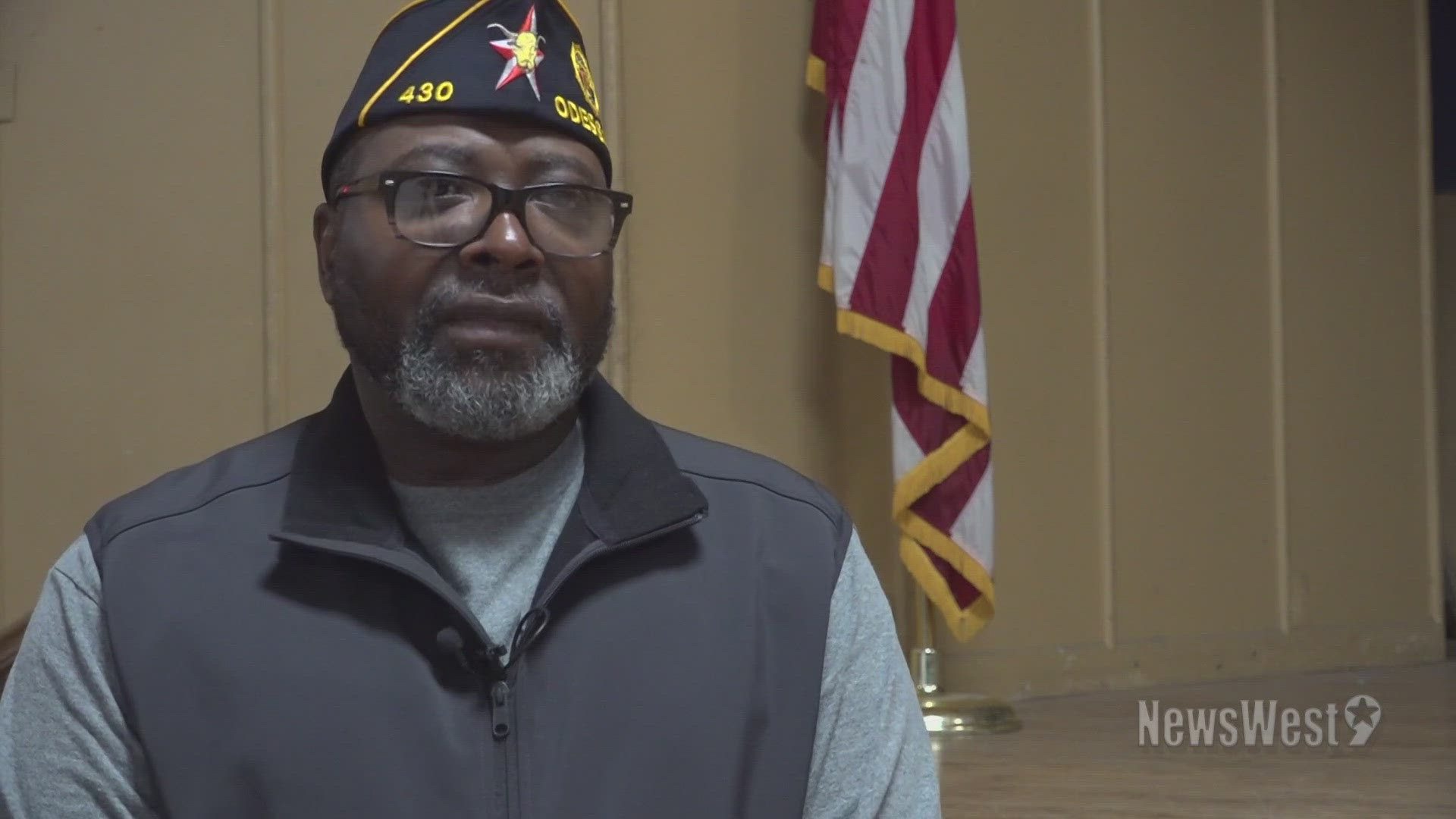

Officers Hamlin and Kim are part of a new team that may be the first of its kind in the nation.

The Regional Domestic Violence Firearms Enforcement Unit is tasked with getting guns out of the hands of alleged abusers – as quickly as possible.

“We’re screening cases right up front, right when they’re filed,” said domestic violence firearms coordinator Theresa Phillips. She works with police, prosecutors, and the courts to determine how many firearms an abuser has and how the Firearms Enforcement Unit can get those guns.

“She’s at highest risk when she’s trying to leave a relationship, seek a protection order and get protection from the court,” Phillips said of the victims who seek protection orders.

The law says that individuals served with a weapons surrender order must turn over all of their guns to police immediately to be held while the case proceeds. The law gives them five days to submit to the court proof – a receipt from a law enforcement agency – that they’ve surrendered their weapons.

Officers tell the person being served with the court order that they can surrender their guns on the spot, receive their receipt, and avoid the possibility of criminal charges later for failing to comply with the court order.

Despite that, a KING 5 investigation last year found that nearly half of accused abusers in King County served with protection orders did not respond to them. The courtroom, where the accused were supposed to appear with proof that they had surrendered their guns, was nearly empty during weekly hearings. Judges had few tools at their disposal to enforce those orders.

The system made the process of seizing guns slow and ineffective and left victims to face an abuser who was angry and armed.

“It takes a lot of courage for a victim to come forward and seek protection from the court,” said Phillips, whose specialty is advocating on behalf of victims.

The Regional Domestic Violence Firearms Enforcement Unit officially launched at the start of this year, with one million dollars in funding from the City of Seattle and King County Council.

In a pilot project during the second half of last year, police and prosecutors police and prosecutors quadrupled the number of guns seized from accused abusers. In some cases, in which victims give specific information about the location of guns, they used search warrants to enter the homes of accused abusers to seize their weapons.

At least two people have been charged with perjury for attempting to conceal their guns.

Theresa Phillips wants victims to know that there are now additional resources available to victims, that will help them develop a safety plan.

“I’ve had the pleasure, it’s the best part of this job, to call and say ‘The guns are secured. We know where they are,’” she said.