Western United: The Life It Lived

The Western United Life Building is not your ordinary abandoned building in West Texas.

Western United Life From Vibrant to Deterioated

Downtown is typically the center point of any city; where there’s nonstop action and plenty of energy. But inside the walls of this building, well, let’s just say things were a little different.

“I always thought the irony of the subsurface library, was that it was in a basement,” David Grace, EVP of Geoscience at Endurance Resources said. “When I was younger I thought that's why it was called the Subsurface Library.”

That’s right: the Subsurface Library, formerly located in the basement of the Western United Life Building. It’s a place where independent oil and gas pioneers became more than business associates… they became family.

“Everybody was like family to me," current manager of the Subsurface Library Mona Koshaba said. "You know, all these guys, they're just like my dads, my grandpas, my brothers.”

Memories of the Subsurface Library live on through the stories of those who share its beginnings and the people who have made connections along the way. But, soon those memories will be all that’s left. The Western United Life Building is scheduled for demolition.

Downtown Midland is growing and changing. Centennial Park is bringing people together.

But there’s still work to be done: The Western United Life Building. It’s been closed since 1996 and has been deteriorating ever since.

The present day appearance, with broken windows and chipped paint, are no indication of what once happened behind these old beige bricks. The building brought people together, and those people helped shape a thriving oil and gas industry, a city, even a nation. The life it lived created family.

For those who have never stepped foot in Midland, the city is known for a few things: being a main hub for oil and gas and also the sheer height of the buildings in the downtown area.

These buildings earned Midland the nickname of “The Tall City”.

“Midland was originally called the Tall City,” Consulting Geologist Jeff Smith said. “Because the building next door-- which was originally called The Hogan building-- and then the Shell building. Now it's the Petroleum Building. It was built, I think, in 1927. And it was the tallest building between Fort Worth and El Paso.”

“[...] you get 100 miles and 50 miles out there on the interstate coming this way,” Geologist Gary Dawson said. “You can see Midland, you can see the buildings.”

“And so Midland became the Tall City,” Smith said.

Despite the nickname, however, the Western United Life Building is being demolished, leaving the Tall City with one less tall building. But it’s not the first-several others have come down in recent years.

The first building in Midland to get demolished was all the way back in 1972, when the famous Scharbauer Hotel hit the dust. The next one was in 2008, when the Midland Savings Building couldn’t be saved. Finally, the most recent one was in 2019 when the Building of the Southwest went south.

The Western United Life Building has been standing since 1948, but has been vacant for several decades, being an abandoned building in Downtown Midland since 1996.

Lee Rousselot, whose father Dick Rousselot co-founded Subsurface Library, was in the building when asked to leave.

“We had, we just signed a one year lease,” Rousselot said. “And then the next month, the owner decided he's gonna close and he gave everybody thirty days notice.”

The building had original plans of becoming Hotel Fuel.

“I thought for a while they were going to turn it into some kind of a hotel,” Dawson said. “But that never happened.”

After several attempts to bring the building back to life, it's left with broken windows and graffiti.

The biggest news coming from this building recently was a tragedy.

“Well, the building has been empty for a long time,” Smith said. “High school kids got in there and went rampaging around in the dark and… one fell down an elevator shaft and was killed. He was one of her [my daughter’s] students. She was devastated.”

“My board and city council decided that the time has come to take it out and create a blank slate for redevelopments that better fit downtown today,” Sara Harris, Executive Director of the MDC, said in October 2022.

The Western United Life Building is coming to an end, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t contribute to the namesake of the Tall City.

The History of the Building From McClintic to Western United Life

All of this information about the building wouldn't be possible without the Midland Reporter-Telegram and the Midland Historical Society.

Standing at 300 West Texas Avenue, it was first named The McClintic building for two brothers, pioneer Midland ranchers Henry and Charles McClintic, who owned the land.

The McClintic Bros, which was also their business name, were sons of former Confederate Sergeant George T. McClintic, a dry goods merchant from Virginia. McClintic owned a ranch in Gaines County that he operated with his two sons.

If you opened a Midland newspaper in the early days, such as the Midland Reporter-Telegram, you’d more than likely see the McClintic name. George was especially a big deal in ranching and real estate, and both him and his family, amongst them his brother “Harry” McClintic, were Midland pioneers.

When George died in 1926 from pneumonia, his $200,000 estate was given to Harry and Charles. Shortly after, Charles announced their plan for their building on a plot of land they owned in Downtown Midland, what came to be known as the McClintic Building.

The big name of the brothers was Charles. Nicknamed Charlie, his name was flooded in the newspapers back then, just like his father. Not only was he a rancher, he was a national guardsman, oilman, church historian, chairman of the local housing committee and served as the Game Commission in Sweetwater in the 1920s.

Despite planning the building in 1926, it wasn’t officially announced until August of 1947, and was first built in 1948. It was seen as becoming one of the most efficient, modern office buildings in the Southwest.

The McClintic Bros previously had an office in the Petroleum Building in the 1930s and 1940s, where they had a business dealing with real estate, city property, farm and ranch lands and oil leases and royalties. They were also oilmen in Midland, Crane and Upton counties since the 1900s.

The building was designed by Wyatt C. Hedrick who also designed the Petroleum Building in 1929. The buildings were connected to each other by a tunnel under Colorado Street. They also shared a building manager, Ralph Geisler.

The permit for the building was a whopping $1 million, which is worth about $13.4 million dollars now. It was originally just going to be 5 floors, but plans obviously changed. In fact, the basement was immediately foundationally adequate for 14 stories.

In September 1948, before the first 6 floors were completed, it was announced the building would expand to 14 floors, and that same year the first six floors were built and went into operation before October 31.

By 1949, the McClintic Building was Midland’s largest building from a space standpoint. It was a 101 by 140 feet structure with 225,000 square feet of rentable space, some space the McClintic Bros rented themselves, as they shared room 108.

The seventh through the twelfth floors along with a two-story penthouse were added in 1951. This made it a 14-story building, concluding the construction.

Unfortunately, Henry died in September 1951, thus ending the McClintic Bros name. Charles stayed in the building in room 105 until 1955. He died seven years later in 1962.

His daughter Isabel Rea was one of Midland’s most talented piano players, and her trust fund ‘The Rea Charitable Trust’ was created in 2009. Its primary purpose was “promotion of the arts”, and the trust gives out scholarships every year to various colleges.

The building changed its name to the Petroleum Life Building in 1954, and in 1957, the current name it is now: the Western United Life Building.

With Midland becoming a major petroleum center in the 1950s and 1960s, more and more oil companies needed offices. By 1950, 215 oil companies had offices in Midland.

Due to the multitude of space, the McClintic Building housed several of those companies.

This includes the Davis Oil Company, Signal Oil and Gas, Burmah Oil and Gas and Tejas Energy Exploration among others. It also housed Permian Computer Systems, GeoMap, Depco Inc, and HBF Corp.

It was also home to county and federal officials, doctors and dentists, geologists, mapping companies, livestock sellers, abstract companies, lawyers, furniture companies, accountants, barbers, insurance companies and surveyors.

There’s stories upon stories in this building-- no pun intended-- from a roof fire to a potential movie being produced in the building… that never happened. Let’s just say Western United Life was definitely lively.

Among the hundreds of people who worked in this building, a familiar face, not just in West Texas history but American history as well, held an office in this building.

In 1952, in room 732, George H. W. Bush was president of the Bush-Overbey Oil Development Company with John Overbey as his vice-president.

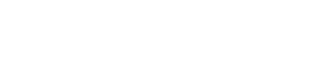

He wasn’t the only George Bush who poked his head there though. His son, George W. Bush also made appearances in this building every so often, as "Arbusto Energy", which turned to "Bush Exploration", had an office in the Petroleum Building across the street around the late 70s and early 80s.

Both of these presidents had their starts in the buildings a lot of Midlanders pass by everyday.

“I was friends with George W,” Smith said. “One funny thing is I went down to Austin one time to take my mother out. And there is a place out there on Lake Travis called The Oasis, which is a beautiful place with all these decks on a cliff. And they don't take reservations. So I take my mother out on a Sunday, the place is packed. It's gonna be a long wait. And we start to leave and somebody runs up and grabs us. ‘Come on! Come and sit with us!’ It was George. George and Laura and Don and Susie Evans. And George asked to sit with us. So we did and my mom, she was happy about it. Then some years later, she was saying how she grew up working in a factory in New York, that she didn't have any use for any Republicans. And I said, ‘Well, how about that friend of mine down in Austin?’ She goes, ‘Oh, yeah, he was a very, very nice man.’ I said, ‘Uh mom, that was George Bush.’ She goes, ‘I sat with a guy who became president?! I didn’t know that!’”

“My dad [Bob Grace] always put prospects together and when he sold the prospect to an operating company,” Grace said. “He always wanted to oversee the mud logging and the wellsite work. And so I would go out to the field with him. I was probably about 13 or 14 and my dad is sitting there in front of the microscope and keeps looking at samples and this young oil man is pacing the floor of the mud logging trailer. And he's saying ‘Mr. Grace, are we there? Mr. Grace, what are you seeing?’ and he said, ‘Son, go sit down over there. And when I see something I'll let you know.’ And I said back then, that man called my dad ‘Mr. Grace’, and I said today we call him Mr. President. It was young George Bush. It was his first well he had ever drilled.

“I found the paperwork in my dad's office after he died. And I found the prospect of the deal and it's signed, ‘George W. Bush, President of George W. Bush Operating’ and doesn't look anything like his signature today. He went to signature school," Grace said.

“That’s where he nicknamed me Dirty Dave,” David Griffin, an engineer that worked for Amarada, said. “He tried to come in there and push me around and I’d elbow him, and so when we went to the White House to visit W, we came in with the entourage and I'm leading the pack and he says ‘Dirty Dave! How are you doing?’ I said, ‘Mr. President, they don't know me by that. Please don't.’”

“At that time, like a lot of other small companies or independents,” Rousellot said. “You come down [to the Subsurface Library] occasionally and you'd see him in there doing his own work. Knew who his daddy was, obviously, but had no idea of what future lies in store for him. But uh, at that time, he was just another client.”

Just another client… who made it. It goes to show that you never know who’s gonna make it, some guy you walk past in Downtown Midland could be President one day.

The Subsurface Library Where a family was formed

One of the most interesting aspects of the Western United Life Building wasn’t on the floors above the ground. It was below.

“My father Dick Rousselot and his partner Kingdon Hughes started the Subsurface Library,” Rousselot said.

In the basement of the building was the Subsurface Library, and this underground library wasn’t like your traditional library.

“Subsurface is an information center for us guys in the oil business, geologists, engineers to create prospects,” Independent Oil Operator Walter King said. “And when we need information that's available in log libraries, that's where we got the information on the scout tickets, and the maps and all the information we could, they would be found in here. Where we can look up Railroad Commission records and identify what we're looking at and find out who owns the leases and who owns the minerals.”

“I know a lot of information was rescued from those being thrown to the dump,” 2023 Petroleum Hall of Famer Edward Runyan said. “That’s absolutely irreplaceable logs, comments, sample logs would have been lost forever if it weren't for the Subsurface Library."

“Back in the day," Grace said. “There was no online resource for data. And so every geologist, and sometimes engineers and a lot of times landmen, they were packed into the Subsurface Library, because it was the only place you could get your data.”

“The Subsurface is a very unique, unique asset," Earl Sebring, who joined the library in the 1970s, said. “No matter how everybody does oil and gas maps on computers, there's always data here that will benefit or kill a prospect.”

“One thing I would say about the Midland Library, we have the best collection of oil and gas libraries in the United States,” said Robert Campbell, who joined the library in 1991.

“And many of us could not have done it without a place to go and this is one of the best ones around,” Dawson said.

The founding duo, Rousselot and Hughes, saw the need for the creation of a geological data library open to all independent oil operators so they would have a chance against the bigger companies. At the time, there were no other such libraries in the Permian Basin.

“A lot of people don't realize the difference in the oil industry, between working for majors and working for an independent,” Carolyn Hobby, who consulted in the building, said.

“The companies I worked for were smaller companies, and not like majors,” Wayne Miller said. “They didn't have the finances to have all the data that the majors would have in house.”

“It really supported the independent side of the business,” Runyan said. “The majors had their own files. They had access to anything that they wanted. We independents, we didn't have that, we needed someplace where we could get all the information they could get that we could get it cheaply.”

“Us independents,” Randy Kidwell, third generation oil, said. “We need the wealth of information that's in this building to help us put together our deals and contribute to the economy here and the betterment of the city and the economy of the US.

“Well, I think they both started way, way back in the 60s,” Koshaba said. “And then as they started expanding they were getting the collections from all the other companies or smaller companies that were getting rid of all their collections, so they needed a bigger place. And then that's when they decided to move into the Western United Life Building.”

Rousselot and Hughes made quite the impression on the oil and gas industry in the Permian Basin.

Dick Rousselot’s son Lee Rousellot, when asked about his father, said, “He was a geologist, as was his father, as am I. So he knew the importance of having access to a database, and his partner King was a land man. They looked at it from different points of view, different parts of the industry, but still recognized the need to serve the underserved small companies.”

“I want to take this opportunity to compliment King Hughes and Mr. Rousselot for having the foresight to start the library at a time when I can imagine how difficult it was to make that happen,” Randy Foster, who joined the library in 1977, said.

“I remember when King Hughes and his wife were sorting scout cards on the floor of their apartment,” Grace said. “But he had an idea and it turned into a very invaluable asset for all of us.”

Due to various factors, in 1997, the library had to move away from the Western United Life Building.

“We moved out of the building, whenever it closed,” Hobby said. “The boiler went out and they told us it was too expensive to fix it. And so we all moved out.”

“It takes a while to find a place,” Rousselot said. “With all the weight of our files and whatnot, you pretty much have to be on ground level, you can't be on an upper floor just because of weight distribution. So you know, that limited a lot of places.”

“...But it was kind of sad,” Hobby said. “It was kind of the end of an era.”

End of one era, but the start of an even better one, as they built their own new, 18,000 square foot building a few blocks away on West Ohio Avenue.

“When we were down there [in the basement], we didn't know if it was raining, the sun was shining but it was nice,” Koshaba said when asked what the new building meant to her.

“Well, this is bigger and newer,” Dawson said. “You know, the other building had plenty of room. The time we all thought it was plenty big down there. But this is way bigger and more spread out and more roomy.”

"When this building was built,” Runyan said. “That was such an accomplishment because it was obvious, we had room to take on a lot of other gifts that came in that was going to be bigger and better. And we were all so very pleased that we were out of the basement and into the sunlight.”

“We were elbow to elbow down here,” Grace said. “It was a pretty small space. The new building that King Hughes and Dick Rousselot built 20 years ago has been really a step up.”

The space is bigger and better now, but the people who remember the basement will never forget the small space where the whole thing began.

Small spaces bring people together even more, which is how the library in the Western United Life Building turned from just a basement to a family.

“Everybody is like family to me,” Koshaba said. “You know, all these guys. You know, they're just like my dads, my grandpas, my brothers. But everybody was just so close, just like a family, and we all took care of each other.”

“At that time, downtown was busy, vibrant,” Rousselot said. “I mean, that's where you made your connections, networked. That sort of thing. And there's many, many independents and small companies at Western United Life, many of which were members of Subsurface.”

“We all went subsurface four or five, six times a day to get data for our geologists and our engineers,” James Corbitt, a former worker for Geomap, said.

“It was very convenient to go down,” Rousselot said. “And it wasn't just about the database, like I said, you're networking and meeting people.”

“It was unusual, working in the basement,” Miller said. “It kind of felt funny, but it was a lot of fun. It was a little crowded. At that time before the library moved to this building, it was very active. People used it and we almost had to stand up to work. So it was enjoyable. If you want to meet somebody or have a meeting, go to Subsurface.”

“Meeting the guys every day, it was the place to meet your friends and visit for a while. We did that quite a bit,” Dawson said. “And you could always get good service. The girls were always helpful and polite and friendly.”

“It was just you’d get on the elevator and you always see someone you knew,” Hobby said. “I was in band in high school, so those are my oldest friends from high school. And when we needed to go hang out we went to the band hall. And that's what this library was like for a lot of these guys. A lot of times they weren't working. They just walked down here to see who was here and they're all still friends.”

“You knew you were gonna find somebody you knew and a lot of deals were I think instigated in Subsurface,” Miller said.

“It's just we've just been through so much,” Koshaba said. “You know, so many so many things. You know, all of us working together.”

“It’s a little different now when you can do it on a computer, you can get the information, but you don't get the contact and, and I think I kind of miss that,” Rousselot said.

Even though the library was underground, it’s safe to say it was the talk of the building in each of the 14 stories above.

The End of the Building But not the City

At the end of the day, a building is a building: a setting. If the bones of this building could talk, it’s safe to say there would be some great stories to tell.

The real memories aren’t entwined with the building itself, but the people you meet and the experiences you have along the way.

“The nostalgia that I have,” Grace said. “It's not so much for the building, but since I started my career here and didn't even know it. When I was 15 years old. I would come downtown, go to the Subsurface Library [...] and pull logs and data from my dad and that sparked something. I ended up getting a Geology degree and being a geologist, I've spent my entire career here in Midland, which there's not many people that can say that didn't have to go do a tour of duty in Houston.”

“Originally got here in 1978,” Corbitt said. “Worked in the building with Geomap, of course it was a very well kept organized building and it was very busy. So there was a lot of activity and then of course, with Subsurface in the basement.”

“I learned a lot,” Koshaba said. “I mean, I'm still learning. My dad was in that building, when he started working for Structure Maps, and I used to go there when I was in high school, you know, walk over there to see him and who didn't know that I was going to be working in that building in the basement in 1984?”

“You know, just a group of guys that we had at Geomap were outstanding, Mona’s dad again, and then I worked in the reproduction area, delivering those maps and those guys were fun to work with, and then also got to watch over the shoulders of the geologists that were also on staff and kind of pick up what they were doing and try to understand what they were doing,” Corbitt said.

Unfortunately, all good things must come to an end. For this building, the beginning to that end started in 1996, and it’s deteriorated since.

“It's been closed for probably fifteen years I bet,” Grace said. “I office right across from the [Centennial] park. And so I'm down here everyday. And I park right around here everyday so I've unfortunately watched it deteriorate slowly over the last few years.

“Over the years I've watched the building and I actually had an office in the building next door in the Building of the Southwest,” Corbitt said. “I spent a lot of time walking this little sidewalk and walking the sidewalk going to Reynolds Brothers Reproduction. So I watched it over these years just kind of deteriorate and we all wondered what was going to happen next.”

Despite all the memories, most of these past building-goers are ready to say goodbye to their old stomping ground.

“I'm not one of these guys that thinks every old building ought to be knocked down,” Grace said. “But when it gets in disrepair like this one has, I don't think any amount of money can save this thing.”

“It's been empty since we left it,” Rousselot said. “So I mean, I understand and it's difficult to go in and renovate an older building.”

“It's been a disaster waiting to happen for years with all the windows all broken out of it,” Dawson said. “And it's time to do something with it. It served its purpose, move it out of the way to build something else.”

“I think it's sad that it went into disrepair five, ten years ago,” Grace said. “But to me I don't know that you can ever read refurb that building, it’s probably full of asbestos. I think some things have a shelf life and I think it has reached its shelf life.”

“It was a beautiful building in its day,” Foster said.

“The architecture and the stone they used,” Grace said. “This stone went all through the building. It was quite a building in its day.”

No matter what gets put in its place, The Tall City still has a tall future.

“So, I will say this,” Grace said. “I've spent my whole career here in Midland. And I've only worked downtown, as I had my office there for the last three years, I’ve always worked out in Claydesta or I worked for 18 years for Henry Petroleum, which is now Henry Resources. And I'm right across from the new park. I'm in the Wall Tower's West Building, and I'm really enjoying downtown, and it's being revitalized. I was against the park. And now I think it's great, it draws a lot of people downtown. Parents come with their kids and play and it's been a good thing.”

“I just think downtown's got a really bright future as a commercial center,” said Nick Masten, who’s grandfather Doug Masten helped found the Subsurface Library. “I don't think it's going away.”

“I think we're gonna have a bright future,” Kidwell said. “I mean, we've got young people. I think the average age is now like 32. So there's lots of exciting things coming down. I think it's attracting people and attracting businesses and the little business is always going to be here, you know, we're right in the heart of it.”

“I'm glad next is here now for Midland because it will only better downtown,” Corbitt said.

“Midland’s future is very bright,” Foster said. “Yeah I don’t think we’re done,” Grace said. “Not in my lifetime.”

Midland isn’t done. And while the Tall City’s future is as bright as it is tall, for every promising future, there’s a positive past, and the Western United Life Building was a cornerstone of that with the memories created here.

Those memories shaped who these people are now. Without the building and the subsurface library, Mona Koshaba wouldn’t have her family and career she has now, Edward Runyan wouldn’t be inducted into the Petroleum Hall of Fame in 2023 and David Grace wouldn’t have followed in his father’s footsteps and made a name for himself in the oil industry.

These sixteen people wouldn’t be having this reunion even after the building closed nearly 25 years ago. Who knows? Maybe George W. Bush doesn’t become president after being yelled at by Mr. Grace.

However you think about it, the Western United Life Building was different from most. It may not have been as towering as the Petroleum Building, it may not have been as historical as the Scharbauer Hotel, but it created memories that lasted a lifetime.

It wasn’t just a building in West Texas, it was a family, and maybe the second and third words in the building’s name are the most important: United. Life.