New immigration rules on obtaining citizenship for children of U.S. service members and government employees born overseas do not affect birthright citizenship, officials said Thursday.

Rules rolled out a day earlier caused confusion among immigration lawyers after a document appeared to show children of American citizens would be affected.

Officials with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services briefed reporters Thursday in an effort to clarify the regulations, and said that if a child is born overseas to a U.S. citizen who is a service member or government employee, then that child will be an American citizen.

There is a policy change and it will affect between 20 and 25 people per year, officials said.

The change is a residency requirement shift and affects U.S. service members or government employees who are green cardholders and have a child while on duty overseas or adopt a child who is not a citizen or are the stepparent of a foreign-born child.

Previously, the agency essentially waived U.S. residency requirements for those people to apply for a passport for their child, but the officials said the State Department would then decline the application for not fitting the requirements.

The policy shift aligns with the State Department requirements and will require a paperwork change. Applications for U.S. service members stationed overseas can still be processed while they are on active duty. The residency requirement mostly affects government employee green cardholders stationed overseas. They would need to move back to the U.S. and live there for three years to five years in order to apply for citizenship for their child.

The highly technical policy manual update Wednesday contradicted parts of an 11-page memo the agency initially put out that implied American citizens were among those whose children would no longer be automatically granted citizenship if born abroad. Immigrant advocates have said the Trump administration has unfairly treated members of the military who aren't American citizens.

Defense Department spokeswoman Lt. Col. Carla M. Gleason said in a statement that the department worked closely with Citizenship and Immigration Services and "understands the estimated impact of this particular change is small."

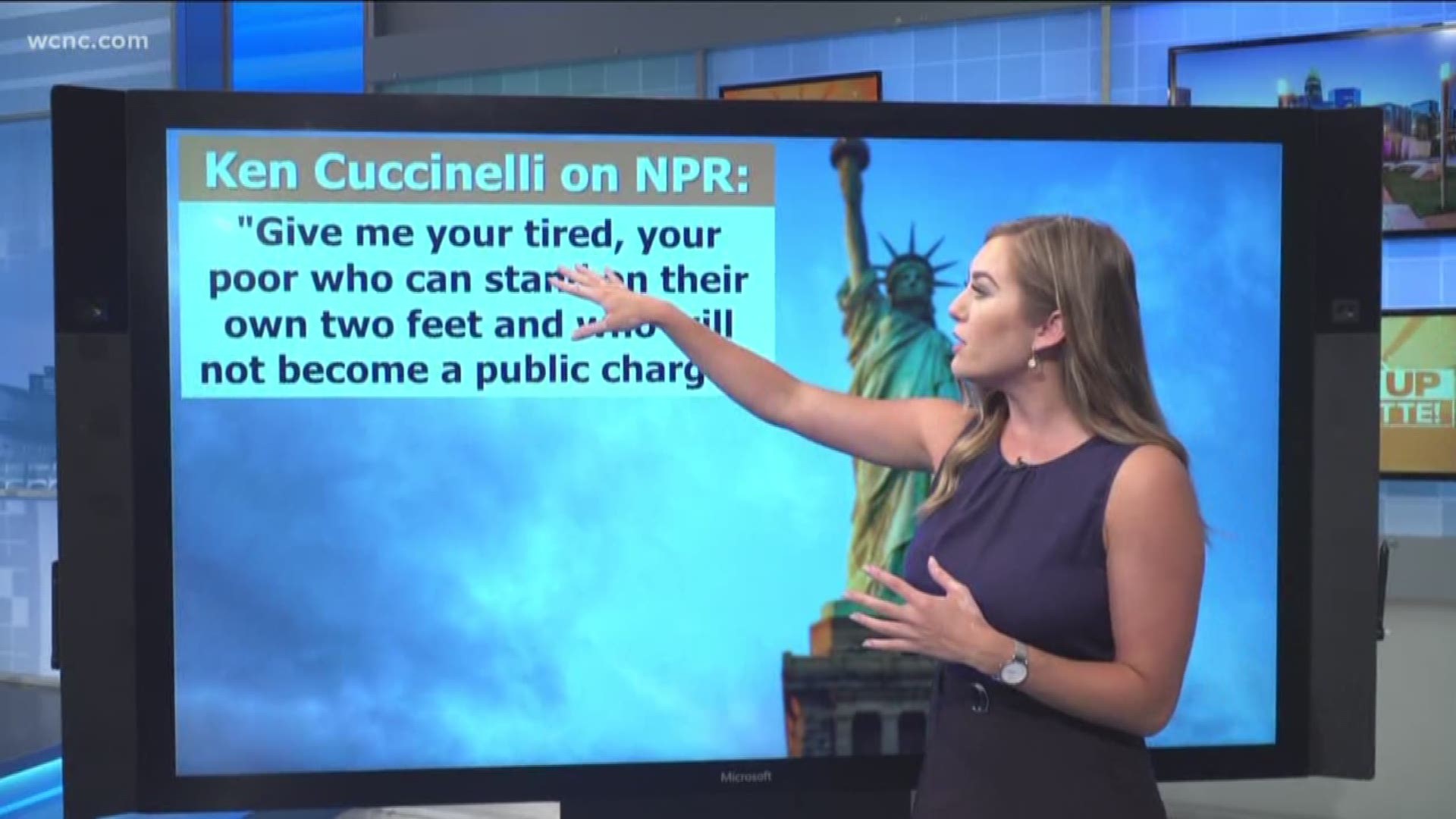

After a barrage of confusion from advocates, lawyers and journalists, the agency's acting director, Ken Cuccinelli, played down the changes in a Twitter statement, saying the update doesn't deny citizenship to children of government and military members.

"This policy aligns USCIS' process with the Department of State's procedures for these children — that's it. Period."

However small, the change was another roadblock that the Trump administration has placed for people to live legally in the United States.

Trump has said he believes a merit-based system of immigration is better for the U.S. than a family-based one, as it is now, and has been working to make changes to how the system works, and follows other more sweeping changes to immigration laws .

Associated Press Writer Julie Watson contributed to this report from San Diego.